Parashat Tazria

♦

Parashat Tazria

Mary Ann Beavis

April 3, 2019

This portion is part of a larger body of ritual law known as the Priestly Code. These rules are hard for modern readers to understand. For example, Lev. 12:1-8 stipulates that a woman who gives birth (tazria, lit. “produces seed”) is ritually impure and must avoid sacred objects and spaces. For a male child, her impurity lasts seven days, and she must avoid consecrated objects and the sanctuary for 30 days; for a female child, the impurity times are doubled to 14 and 60 days. After purification, the woman must bring a sin-offering (hattat) to a priest to complete her purification. The legislation seems not only incomprehensible—why would the life-giving event of giving birth (Gen 1:28) require purification, let alone a sin-offering? — but also sexist: why the distinction between the treatment of the mothers of sons versus daughters?

To understand these laws, it is important to realize that ritual purity/impurity does not have anything to do with hygiene or morality. Ritual purity refers to a state of fitness to engage in sacred activities or enter sacred spaces. Purity laws apply “to bodily states that render persons, especially priests, ritually fit or unfit to engage in acts of worship, especially in the context of offering sacrifices in the temple. Ritual impurity could be incurred through disease, contact with a corpse, bodily discharges (including, but not confined to, menstruation), and sexual activity (which involves bodily discharges for both men and women)…Good actions (e.g., caring for the dead, giving birth, having sex with one’s spouse) would inevitably incur impurity, which could be dealt with by appropriate rituals and the passage of time” (Beavis and Kim-Cragg, 132). The doubling of the mother’s purification period after the birth of a daughter has been explained in different ways, e.g., “a girl potentially doubles the ‘life-leak’ that has taken place, … since she will one day be a childbearing woman and will herself confront the life-death continuum” (Fox, 562, but note Judith Romney Wegner (40), who sagely notes that “no satisfactory explanation of this discrepancy has yet been found”). It might be speculated that the longer period of seclusion gave mothers additional time to bond with their baby girls. Commentators are similarly puzzled over the reason for the sin-offering, since ritual impurity does not constitute sin. Plaut opines that “The reference here is to a ritual purgation and nothing else” (826). The Midrash suggests that the hattat might be necessitated by a woman’s inadvertent sin while in labour: “she might have vowed, ‘I’ll never let my husband come near me again!” (Plaut, 827).

Unfortunately, Christian interpreters have often misinterpreted these laws as evidence that Judaism is misogynist and superficially legalistic. In their ancient Israelite context, the Priestly Code protected the sanctity of the holy community, as the moral laws of Torah continue to do.

For Reflection and Discussion: [1] What are the implications of this commentary for interfaith dialogue?

[2] Do you agree with Amy-Jill Levine that Christian leaders and teachers sometimes inadvertently perpetuate anti-semitism by using Judaism as a foil for Christianity? (Levine, 119)

Bibliography: Beavis and Kim-Cragg, What Does the Bible Say? (Eugene, OR, 2017); Fox, The Five Books of Moses (Jerusalem, 1976); Levine, The Misunderstood Jew (San Francisco, 2006); Plaut, The Torah (New York, 1981); Wegner, “Leviticus,” Women’s Bible Commentary (London/Louisville, 1992).

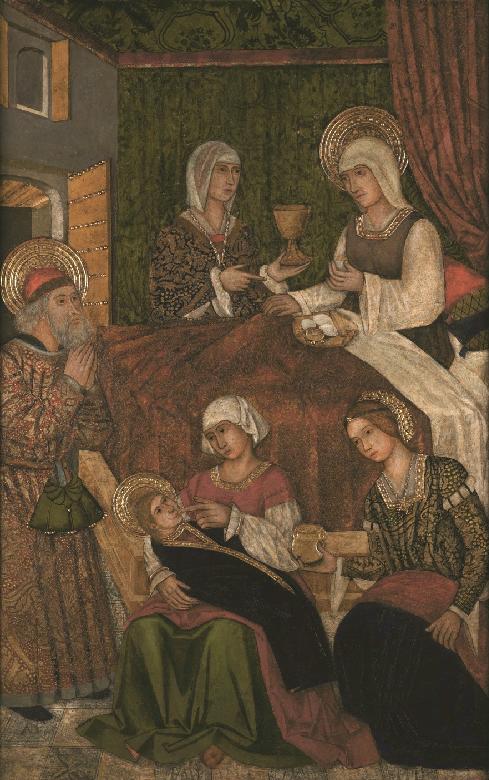

Altarpiece of St. Anne, St. Velery and St. Vincent. Birth of the Virgin Workshop – Domingo Ram, 1475/1499

Source: Google Arts & Culture

This week’s teaching commentary is by

Mary Ann Beavis,

PhD, Saskatoon, Canada, Bat Kol alumna 2004, 2006, 2012

PLEASE NOTE: The weekly Parashah commentaries represent the research and creative thought of their authors, and are meant to stimulate deeper thinking about the meaning of the Scriptures. While they draw upon the study methods and sources employed by the ISPS-Ratisbonne, the views and conclusions expressed in these commentaries are solely those of their authors, and do not necessarily represent the views of ISPS-Ratisbonne. The commentaries, along with all materials published on the ISPS-Ratisbonne website, are copyrighted by the writers, and are made available for personal and group study, and local church purposes. Permission needed for other purposes. Questions, comments and feedback are always welcome.

Share this with your friends

Share on facebook

Share on google

Share on twitter

Share on whatsapp

Institute Saint Pierre de Sion – Ratisbonne – Christian Center for Jewish Studies

Congregation of the Religious of Our Lady of Sion

Contact us:

secretary@ratisbonne.org.il

26 Shmuel Ha-Naguid Street – Jerusalem

Subscribe to Newsletter

No responses yet